“I was born condemned to be one of those who has to see all sides of a question.” says Larry Slade, a too-scared-to-live too-cowardly-to-die drunk in Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh (which is not a horror movie, but would be a killer title for one).

Whenever I have to form any sort of definitive opinion and express it in say, a Substack or on a podcast, I feel similarly condemned. I love to talk about movies, and I love to write about them; and maybe it’s the fact that I love them that makes me unable to form any definitive conclusions about them, my own tastes, that don’t feel grossly hypocritical. Like Larry Slade, I’m condemned to see all the sides.

Maybe it’s not the best idea to start a piece of writing by talking like I’ve been forced at gunpoint to write it. I’m not forced — on a deadline, perhaps — and the fact of it is that this is a subject that I want to be talking about and which I think I know a moderate bit about. This is gift, and this is curse: because I know a bit about the subject, and because the subject is a subject of my passions, it is all the more difficult for me to write about in a way that fully encompasses all of my feelings.

This aforementioned subject is the horror genre. In particular, horror film.

I know the early trends and I know the modern trends; I know the masters and the makers and the corner-office shakers, names like Stephen King and Jason Blum and John Carpenter, and the way each is struck between the worlds of commerce and creation.

I have my opinions, and I would love to be able to draw definitive and consistent conclusions from those opinions, but again, I’m condemned to see all sides, yada yada. I like to be entertained; I like horror when it entertains. I like to be made to jump a bit in the theater. I like Chucky; I don’t like The Conjuring; I will watch a few of the Saw movies every year. I think horror peaked with The Exorcist. I think despite his weak back-half-output, John Carpenter should come out of retirement. I think Stephen King is the best popular American author of his generation, at least until I reconsider what “best” and “popular” mean. I think horror is best when it simmers. I think horror might not be what it used to be. I like the classiest of classy horrors.

But I love “trashy” horror too, in all senses of the word: trashy low-budget, trashy mid-budget, trashy commercial fare from start-up studios like Blumhouse, even if I know it’s not-so-good. To quote Former Little Rascals star Donald J. Trump on the subject of Diet Coke, “I’ll still keep drinking that garbage”.

This Former Prez - Diet Coke dichotomy seems to be prevalent in the horror fandom, a community which is, generally, very un-pretentious about classic schlock and, conversely, overly-critical of anything new. Step onto any dedicated horror forum (there are at least fifty different subreddits talking about horror films, whether dedicated to specific franchises or to the genre in general) and find the prevailing belief that they just don’t make them like this anymore. And I don’t disagree with the majority opinion — a lot of the horror movies coming out today are bad, but is there necessarily a reason that today’s bad is any worse than yesterday’s bad?

Many arguments have been made about the over-reliance on the jump scare being the thing that definitively “ruined” horror, but how do you square that away with beloved classics such as Evil Dead (1981), Evil Dead II (1987), An American Werewolf in London (1981), The Exorcist III (1990), Candyman (1992), Alien (1979), Dawn of the Dead (1978), Day of the Dead (1985), Texas Chain Saw (1974) and Texas Chain Saw 2 (1986), The Thing (1982), plus all the Freddys, Jasons, Chuckys, and Michael Myers’ you could ever want, films from a so-called “better age” of horror mourned in places like r/horror and other sub-forums, that use frequent jump scares to great effect? How do you create a consistent ideology out of anything, especially when you’re talking about something as subjective as art?

What these questions all run back to is, how do we talk about art? Is there a way that we must talk about art — role of the critic, is to toss away subjectivity, rate objectively, as much as one can, isn’t it? But what is objective? And when are you being too objective? Too subjective?

So, this became an article less on the state of horror, and more on the state of how we talk about horror: what horror was (generally), what horror is (generally), and what horror could be (generally).

What Horror Was

We’re talking general trends here.

Early-ish cinema (re: made before, say, the advent of the Schwarzenegger) is slow. You and I might not think that — we who actively seek out new old films — but the truth is, in the eyes of a culture whose attention spans have been so warped not just by thrill-a-millisecond action and horror and superhero films but also by the TikTok-ization of “content” and the endless doom-scroll, most movies made before circa Predator seem downright glacial.

The pacing of these classic films is often not actually glacial (I won’t deny that sometimes, yes, movies can be boring). Rather, they are deliberately-set at slower tempos; that doesn’t make them dirges. It is not the films’ fault (again, often, not always) that they seem boring; it’s the fact that the nature of moviegoing and the nature of being entertained has so changed in the intervening decades that we can’t seem to tune ourselves to the general wavelength of a slow-burn, save for Clockwork Orange-style reconditioning of our own expectations. Even if you train yourself to expect slow, patient pacing, it can often be a challenge sometimes to pay the full attention demanded. Even though I force myself to keep my phone in another room when I watch a film, I still feel the urge to duck away and doom-scroll during Casablanca.

So if you’re going in to Frankenstein, or Dracula, or Cat People expecting to be scared in the same way seeing a freaky-ass Conjuring demon might scare you, you’re probably going to be disappointed. You can appreciate the films, and absolve them any of their faults, with the simple acknowledgement that I am a product of my time, and the film is a product of it’s own.

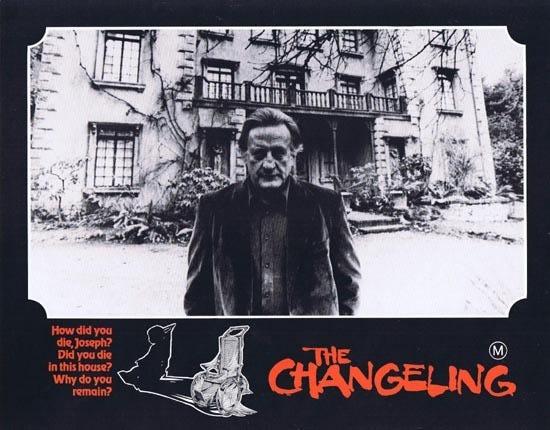

Though this is a tie-in to Peter Medak’s 1980 film The Changeling, I’d like to begin first by citing an example of how our modern heart-pumping get-the-sex-drive-up-by-getting-you-spooked slashers have affected the way we might watch one of the very first slashers.

Bob Clark’s Black Christmas, released in 1974, is often cited by film historians as the first slasher film. This is an oversimplification, but it’s an oversimplification that works (of course acknowledging the giallo films coming out of Italy and the drive-in films playing in front of backseat make-out sessions and the prototypes of Psycho and Peeping Tom) at least in part due to it’s outsized influence (despite middling financial success) on films such as Halloween and thus the further genre as a whole.

Black Christmas is a classic set-up that hadn’t, in 1974, become classic yet: in Bob Clark’s film, a group of sorority sisters (including stand-outs Margot Kidder, Olivia Hussey, and Andrea Martin) are hunted one-by-one by a serial killing pervert, unseen save for his piercing eyes and his probing hands.

In an early scene, with only one sorority sister down-for-the-count and a few nasty phone calls, the housemother Mrs. MacHenry (a sadly too-soon-dispatched Marian Waldman), is probing the house for one of her many stashes of liquor, a diversion which takes her to the medicine cabinet of the upstairs bathroom.

We’ve seen medicine cabinets and their mirrors in horror movies before, perhaps far too many times. It’s a genre staple — some would say “cliche”, though the fact that these scenes always make someone in the audience jump would say otherwise. The scene, unless the film is intending on playing against our expectations, always goes like this: character looks in mirror, nothing scary; opens medicine cabinet, we can’t see mirror, what could be happening unseen, something scary?; closes medicine cabinet, there is something scary!

Mrs. MacHenry, of course, does not know that she is in a horror movie, and even if she did, probably she would not have had the cultural cache to know that opening her mirrored-medicine-cabinet often means certain doom for old ladies alone with serial-killing perverts. Expectation takes over when you’re watching this scene; your mind fills in the blanks; you might as well let your eyes glaze over.

I’ve clenched all the clenchable parts of my body, at this point. I’m used to horror movies but I’m still not used to them — not entirely, at least, and not always immune (I must as well admit that the susceptible audience member who jumps at the sudden appearance of the killer in the mirror is, more than likely, me). Then despite the fact that she is in a horror movie, and despite the fact I’ve already begun to clench in all of the usual clenchable parts of my body, she is completely safe when she closes the mirror: there is no one behind her, and she lives to see another day (well, another five minutes or so).

I caught myself thinking, “What an interesting way of building tension — playing out a long scene in the bathroom, making us expect something in the mirror, but nothing ever appears”.

But then I asked myself — was that an established convention of the genre, then? Probably such a scare had happened, but was it a well-known enough terror tactic that an audience would go in expecting it? Or was that just my modern pre-conceptions of what a horror movie is supposed to do talking, making me clench when maybe I didn’t have to clench?

I enjoyed the movie the first time around, but I loved it the second, and the third, and now it’s a yearly tradition, just like watching Halloween on AMC in October. The problem with my first watching, which left me underwhelmed, was the fact that, while I knew I was walking into a haunted house (all horror movies are haunted houses), I hadn’t asked myself the crucial question for understanding horror on it’s own terms:

What kind of haunted house am I walking into?

Haunted Houses

There are literal haunted houses, and there are metaphorical haunted houses.

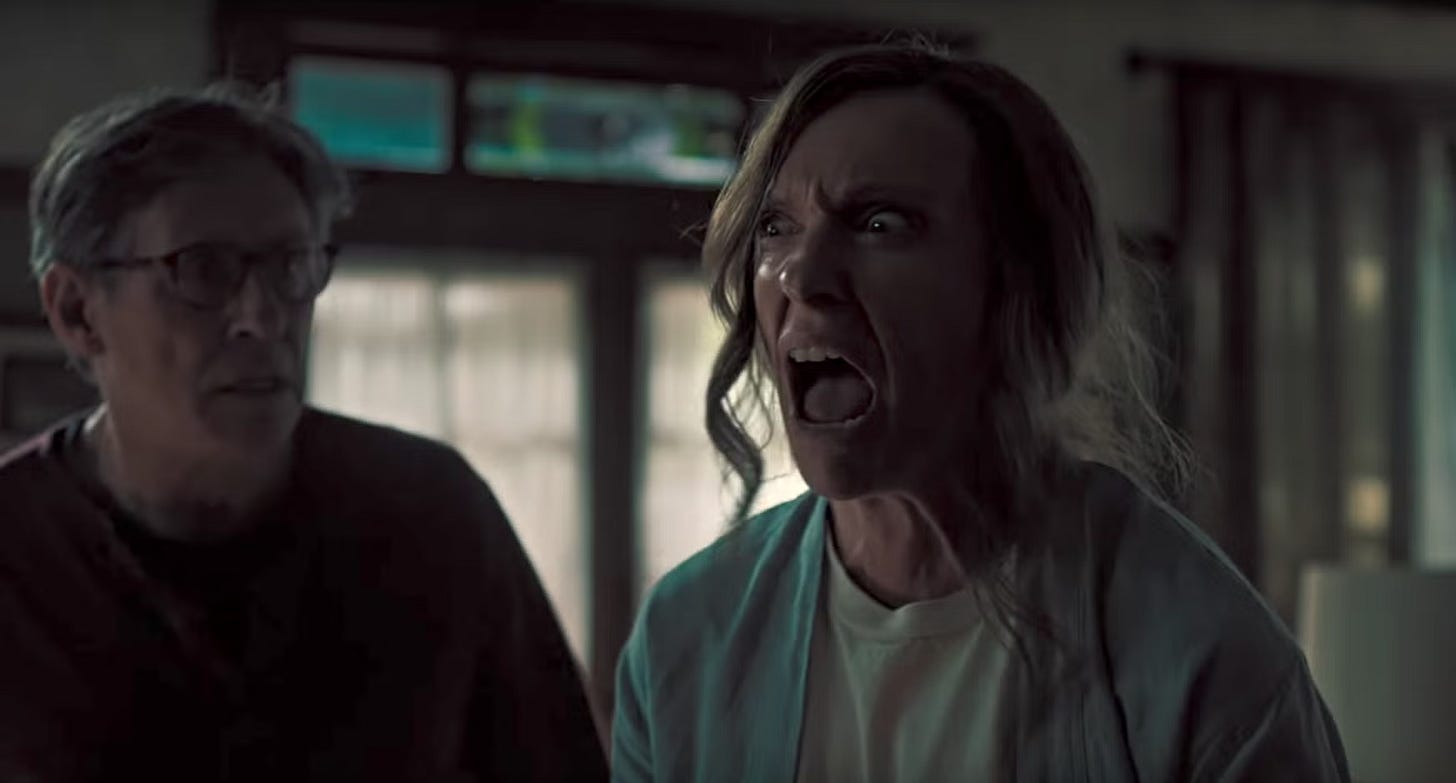

Literal: There are haunted house movies which are, textually about houses which are in the throes of an active haunting; your Amityville’s and such. Then, there are movies about “haunted” “houses”, metaphorical type A. These are the “trauma” horrors, what might be referred to as the A24 house-style as established in recent years (again, a flattening by marketing term); your Hereditarys, your Talk To Mes, your Babadooks. While most horror is at least subtextually about trauma and trauma response, this specific subset type A makes said bad-feelings the text — take, for example, Florence Pugh’s character in Midsommar having explicit visions of the murder-suicide of her sister and parents.

The third type (metaphorical type B) is the “haunted house” film. It would be easy to call these “roller coasters”, as Scorsese famously referred to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The better term for these might be “haunted house” movies, a term which I feel can be utilized in several different ways. To refer to this new brand of horror (which, despite many semi-movements, has remained the predominant brand of market-viable horror), you wouldn’t even have to create a new term; just change the colloquial meaning. The 70s may have been the decade of the haunted house in the Amityville meaning, but all the decades that follow have been “haunted houses” in the duct-taped-together maximum-scare you-can-see-the-strings-but-who-cares-when-you’ve-got-all-this-stuff-jumping-out-at-you mode.

Where The Changeling succeeds is in successfully combining the three different “types” of haunted a movie can be, allowing it’s literal haunted house to deliver genuine thrills as well as serving as a greater metaphor for George C. Scott’s character’s own grief.

The Changeling exists on a strange precipice. Peter Medak’s meditative-but-still-downright-terrifying thriller comes two years after Halloween, one year after Amityville, and in the same year as Friday the 13th, seeming like the last portage of the slow-burn 70s-horror before the oncoming sea of the 80s slasher.

It might be wrong to say “They don’t make them like this anymore”, but certainly they didn’t make them like this as often.

Following the tragic death of his wife and young daughter (a brutal and unflinching scene that draws to mind a much bloodier film), George C. Scott’s John Russell, a composer, takes a job teaching in Seattle, far away from the memories his now-empty New York apartment conjures.

Living now in a decaying mansion probably far too unwieldly for a single man to occupy, Russell finds the perfect avenue to blow off steam: figuring out what that weird banging noise is, and then helping the source of that weird banging noise, the ghost of a child killed in the house nearly a century before, find peace by solving his murder and the cover-up involved.

While The Changeling functions more like a mystery novel than a horror film, it’s not without it’s fair share of terrifying moments, including a tense-as-hell seance that culminates in one of cinema’s great jump scares; a giallo-esque red-blooded car crash sequence; and the creepiest wheelchair in fiction since Mr. Potter tried to take over the Bailey Building & Loan. Though I don’t begrudge anyone who might not be thrilled by the film, it was one of very few horror films that I watched between my fingers, as an adult.

As stated above, The Changeling is able to, without feeling at all muddled in tone, combine all three major tenets of horror (the haunted house “types”):

A protagonist threatened by a supernatural and/or malevolent force

A story that provides consistent, if infrequent, thrills

Deeper themes that echo a more personal “haunting” — whether that be personal or societal

If these seem at all like fairly basic genre elements, that’s the point. But in the post-meta cultural landscape, a lot of horror films have lost sight of these fundamentals, or unevenly applied them in ways detrimental to the film’s overall effect.

Hereditary, in my personal opinion, is to-date the most effective pairing of these styles. It’s slow, yes, but it’s a film that puts the burn in slow-burn. Even before the literalized demons take their possession of the family, it’s still a deeply uncomfortable piece of film, with certain sequences, like the beheading and it’s aftermath, the now bordering-on-iconic I AM YOUR MOTHER! speech, inducing just as much if not more dread than all the seances and husband-burnings the film provides. The same can be said for Aster’s Midsommar, and The Babadook, and many of the so-called ‘A24 Horror’ that can easily be identified as the newest and most current wave.

But that’s a discussion for another bi-week.

In two weeks, I’ll be writing about what horror is, and where I think the genre is going to go moving forward. I’ll be using Barbarian as a jumping off point — discussing specifically how it represents one of the best ideals to which modern horror can be, blending current sensibilities with well-established and still-effective tropes.

In the meantime, be sure to subscribe for future articles, and visit the Spineless RSS feed to subscribe to our bi-weekly audio feed.

Awesome!